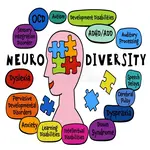

Different, not deficient, The Gift of Neurodiversity

I remember my school friend A. She was brilliant—without question, one of the brightest in our class. Yet, there was something about noise that dysregulated her, as though the hum of the world around her was too much for her senses to contain. In those moments, she would retreat into herself, a whirlwind of energy and sharp wit temporarily dimmed. On other days, her vitality was unmatched, and she was the life of the party, her infectious laughter filling the room. But this same high energy, this untamed spirit, would often become a challenge. In quieter moments, when focus was demanded, it seemed to elude her, slipping away as though it were a butterfly too swift to catch.

Before exams, she would often call me. I knew the drill. A mix of innate desire to study and an inner struggle to hold attention. Her mind, it seemed, was a kaleidoscope—constantly shifting, always drawn to something new. One moment, she would dive into a book, her focus narrowing so intensely that her thoughts would crystallize into brilliance. The next, something would catch her eye—an idea, a question, a fleeting thought—and she would veer off, leaving her studies abandoned like an unfinished painting.

As we pursued our degrees together, her mind’s brilliance and unpredictability began to bother her. It wasn't the chaos of creativity she feared, but the inability to control it. She sought answers. And eventually, a diagnosis: ADHD—Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

For many, the biomedical model would offer Ritalin or Adderall as solutions. But then, there is the work of Gabor Maté, whose pathbreaking book Scattered Minds challenges the clinical narrative. In his work, Maté illustrates that ADHD is not a mere disorder; it is, in many cases, a response—a deeply human adaptation to the world around us. Maté proposes that the roots of ADHD may lie not in a miswired brain, but in a misattuned environment. He points to the parent-child dynamic, where emotional neglect, a lack of containment, and an absence of attunement overwhelm the child’s nervous system. The areas responsible for emotional regulation and focus, critical for adulthood, become underdeveloped, creating lifelong challenges when these faculties are needed most.

But let’s pause here. I am not dismissing psychiatry, nor am I suggesting that medication is inherently wrong. In fact, for many, the combination of medication and talk therapy can be life-changing, helping them find balance where there was once only turmoil. What I am advocating for is a shift in perspective—a reminder that the development of our brains is shaped not only by biology but by the nurturing we receive. Our brains don’t just function differently due to disorders. They develop differently based on the environments they grow in.

Neurodiversity, at its heart, is about celebrating this difference. It’s a call to understand that not everyone fits into the same mold. Just as no two children, even in the same family, require identical parenting, so too do children with neurodiverse traits need distinct approaches. One may thrive in structured environments, while another flounders. One might find a sense of security in routine, while another is suffocated by it. A visual learner might be lost in a theoretical text, and a child with dyslexia may feel defeated by the very act of reading, a simple task for their neurotypical peers. These differences, when misunderstood, often get converted into hierarchies—social, educational, and familial. The same logic applies in every sphere of life: the idea that differences need to be “fixed” or “corrected” can lead to a painful reduction of individual potential.

Take, for example, the classroom. Picture a teacher standing at the front, explaining a complex math problem on the board. For a neurotypical child, this visual and verbal explanation may be enough to grasp the concept. Their attention shifts seamlessly from the board to the teacher and back, and they work through the problem with relative ease. For a neurodiverse child, however, the classroom environment might be overwhelming—the hum of the fluorescent lights, the rustle of papers, the shifting movements of classmates—making it incredibly difficult to concentrate. The neurodiverse child may need more time to process the same problem, or may need to be given additional support like written instructions or a quieter space to work in. It’s not about a lack of intelligence; it’s about how the brain processes information and the different ways in which focus and attention are engaged.

This is a point I vividly recall from a lecture in my M.A. course on Politics, Resistance, and Transformation. The professor urged us, “Question every situation where differences are transformed into hierarchies.” That lesson resonates deeply in the context of neurodiversity, where differences in how we think, learn, and process the world can be viewed as a hierarchy—one that values the “norm” above all else, creating a framework where those who diverge are marginalized.

In raising awareness for neurodiverse experiences, I don’t wish to ignore the real challenges they come with. It’s not easy—especially for parents, teachers, and caregivers who are constantly learning on the go, adapting their approaches, finding their own balance. But this complexity doesn’t erase the richness of these differences. The child with ADHD or autism isn’t a broken piece of the puzzle, but a unique piece that may simply require a different kind of space to flourish.

Take Eileen Miller’s powerful account in The Girl Who Spoke with Pictures: Autism through Art, where she chronicles her daughter’s journey with autism from ages 3 to 17. Her daughter, unable to speak conventionally, revealed her thoughts and emotions through art. Through carefully attuned observation, Eileen uncovered a language her daughter spoke through colors, shapes, and strokes. It wasn’t just a story about a child’s struggle—it was about a caregiver’s commitment to seeing beyond the surface, understanding that there was an inherent communication even in what appeared silent.

Yet, in countries like India, where material and emotional support systems are often lacking, raising a neurodiverse child becomes even more difficult. The burden on parents is magnified when resources are scarce, and the task of supporting a child with special needs becomes an uphill struggle. It’s a constant balancing act, especially when there are multiple children to care for, each requiring a different set of tools and approaches.

This is where the need for systemic change becomes clear. It’s not enough to have individual schools or caregivers providing support in isolation. The ecosystem—the network of teachers, special educators, and parents—needs to be strengthened, supported, and sustained. We need spaces that nurture not just the child, but the caregiver, the teacher, the community as a whole.

Neurodiversity, when fully understood, locates the individual not as someone struggling against their circumstances, but as an agent with unique strengths and challenges. The child with ADHD is not simply suffering from a deficit—they are navigating a different, complex world that demands a different response. By broadening our understanding of how the brain can develop, we are better equipped to offer environments that help these individuals thrive, not just survive.

To do this, we must ask ourselves: How can we build a society that celebrates neurodiversity, not as a challenge to overcome, but as an integral part of the human experience? How can we create systems that see differences not as problems to be fixed, but as variations of strength and potential? The answer lies in education—educating ourselves to revise our conditioned lenses, to see the fullness of what it means to be human in all its neurodiverse forms. In doing so, we create spaces not just for the “special” child, but for the potential of all minds to grow, flourish, and contribute in their own unique ways.

Ms. Meghna Joshi

Psychodynamic Counsellor